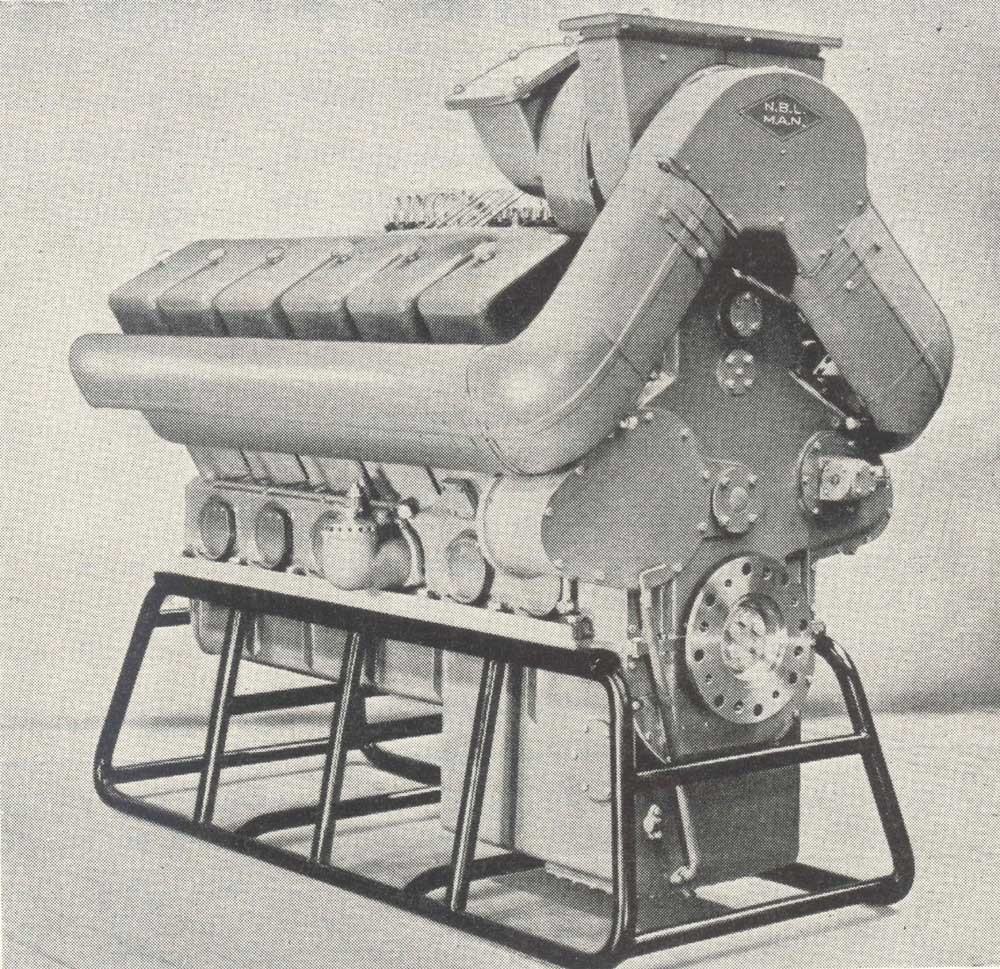

NBL MAN L12 V18/21 Engine

Engine 220

We have 7.5 tonnes of steel that will one day power D6358 and it’s in much better shape than we dared hope! The plan for one working weekend was to investigate what we had and what actually worked, or looked like it would work. As each stage passed we were encouraged to go a little further – starting with an external examination which showed that there were no nasty cracks or dents, and no butchery that we could see.

Next we removed the rocker covers to examine the valve gear – which we found to be in excellent shape.

Moving to the top of the engine, we checked the governor which we found had a partially seized throttle linkage, which we are sure will free-off relatively easily. The more worrying part is we don’t know what it is like internally so will have to remove it and send it away for examination/refurbishment.

Behind the governor are the twin fuel pumps. These have been subject to an aborted attempt at removal in the past, the fuel inlet pipes have been disconnected letting the moisture in the air get into them and the mounting bolts had been partially removed. The bolts were re-tightened and the couplings between the drive and governor were examined and found to be in good condition. The pumps will also need to be removed and overhauled.

The Napier turbocharger was examined externally and the oil was noted to be clean. The exhaust stack and inlets were covered for the time being, as the inlets had been worryingly uncovered when we received the engine and so, again, we will need to get the part thoroughly overhauled.

The next item to receive attention was the sump drain. The drain was cracked open and, yes, we did get some water coming out, but, not a great deal – a few pints at the most. A sample was drawn to analyse to see what kind of condition the bottom end is in.

At this point it was decided that the oil was sufficiently good that we could test the priming pump, so checking whether the lubricating system was functioning correctly. The manual pump was operated and surprisingly we achieved 50–55 psi. We had one leak – a flexible hose supplying the Governor – which was quickly the subject of a temporary repair. We checked that oil was being supplied to the rockers and were pleased to see that it was being lubricated correctly.

The possibility of barring the engine over was discussed and considered feasible, so all the decompression valves were removed complete and will be subject to further work in the future. Once out, the combustion chambers inside the heads were examined as far as possible (which admittedly wasn’t very far) but they certainly looked in acceptable condition.

We next applied a large Stillsons to the stub of shaft attached to the flywheel and attached an extension expecting a big heave to be required to move it. In fact just leaning on the Stillsons moved the crank! We were amazed! The next task was to pump up the lubrication system and try turning it over, which was highly successful. We gave the engine quite a few turns and were pleased to hear the whistling of compression escaping from the decompression valve cavities. Of note was the fact that there was no moisture expelled with the compressed air, so proving that the cylinders were dry; a major relief!

At this point we decided to step back and consider our next moves.

We think that the engine is in good enough condition to attempt a start with certain work carried out. We need to have the examination and refurbishment of the governor, fuel pumps and turbo completed before there is any chance that we will try a start. That will cost money, but, it should be money well spent. In the meantime, we will get the oil analysed and carry out a compression test. If these both come back as acceptable, we will then attempt to motor the engine on the starter, … which we need to buy! Once the components are returned, we will fit and time everything, bleed the system and attempt a start.

We will need some sort of radiator if we want to run for more than a few minutes of course – another expense, but when the time is right, one we really should look at closely.

Engine 220 History

No: |

Loco |

Fitted |

At |

Removed |

At |

Experiments |

Hrs |

Note |

220 |

D860B |

16/01/64 |

– |

|

|

268 |

|

|

|

|

D853A |

29/10/66 |

Laira |

1968 |

|

330/354 |

|

High lubricating oil consumption |

|

|

D850 |

04/03/69 |

OOC |

03/69 |

OOC |

|

75 |

Throwing oil |

NBL MAN Engines

It might be interesting to take a brief look at this particular engine type. Designed and manufactured in Germany by M.A.N (Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nurnberg). The most immediate predecessor to the L12V18/21 was the MAN L12V17.5/22 of 800 bhp at 1400rpm, some of which were used by the German Railways (DB) in certain class V80/V100 locomotives, as well as in locomotives exported for use overseas. A need for an engine of higher power output was required to compete with rival manufacturers, such as Mercedes Benz and Maybach, which led to the development of the higher rated engine, designated L12V18/21 specifically for potential use by DB in the new V200 class locomotives then under development.

Fortunately, and in spite of the passage of several decades since the last surviving example of Class 22 was scrapped, we knew that certain surviving engines were still in existence, and felt that obtaining at least one of them was an absolute must in order to secure a beating heart for the locomotive. We are of the opinion that no substitute engine would correctly represent the lost sound of a North British mainline diesel locomotive in action. We continue our search for further examples, some of which we’re sure must survive.

The society believes, and has believed from the very inception of the project, that the use of an original engine actually used in a Class 22 – which formed the essence and life blood of the locomotive – would be vital in order to accurately recreate the 59th member of the class. Examples of the same engine type were used in the similar Class 21 locomotives, the D600 “Warship” locomotives, of North British design and build, as well as the North British built version of the Krauss Maffei /Swindon “Warship” design, often known as D833 type and later as Class 43, although none of them survived long enough to be renumbered. German built engines were also used in the “Blue Pullman” diesel electric multiple unit trains, each set having one per power car for a total installed 2000bhp per set.

The L12V18/21 was issued in normally aspirated form (no suffix) and supercharged (Suffix A – Aufladung – Supercharged). All NBL built engines were to the “A” specification – i.e. fitted with turbocharger except that for UK customers, Napier turbochargers replaced MAN blowers and CAV injection equipment replaced Bosch (which were identical anyway). Confusing the issue, NBL re-designated “A” to “S” – Supercharged. There seems to be no evidence that a “B” specification engine ever existed, “BS” simply indicated that it was a British (B) built Supercharged (S) model, in the same way that the CAV BPE injection pumps were British built Bosch PE pumps. Taking the foregoing into consideration it is easy to understand why writers may previously have described A & B series engines as being different, rather than a different designation for the same engine. It seems that many of the so called changes in specification such as the increased crank pin diameter may have taken place as a result of the development process for the new engine, although it is certain that modifications would have been made and incorporated into later engines as a result of experience.

Although of relative simplicity many, feel that the design was later developed to the maximum potential of its type, perhaps in fact even in excess of that, which might account for its reputation for unreliability when driven to its maximum rating. The type was originally given a railway rating of 1000bhp at 1440rpm with a 1 hour rating of 1100bhp at 1500rpm. Experience with the engine, including a continuous 80 hour test run by DB, resulted in a revision of the railway rating to 1100bhp at 1530rpm. This was a high figure for an engine of conventional design and might have led to unreliability issues when run at full output for extended periods. Lack of piston crown cooling has often been cited as a further weakness, however study of the plans will show this to be at least partly false, as a drilling in the little end of the connecting rod was provided to spray a jet of oil onto the underside of the piston crown for the purpose of cooling.

In order to allow them to compete in the manufacture of diesel locomotives for British Railways, a licensing arrangement was put into place allowing North British to manufacture a range of oil engines of MAN design for the home market. NBL were also able to manufacture Voith Hydraulic transmissions under a similar arrangement.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Engine No. 220 – built under license by North British in Glasgow – is type L12V18/21BS and was rated at 1100bhp at 1530rpm when in service with British Railways.